Of the host of challenges facing Vancouver’s aging Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels – including conversion, dilapidation, and demolition – fire is the gravest. On April 11, 2022 the 115 year old Winters Hotel in Gastown burned down, displacing 143 residents and several businesses. Tragically, two people who lived in the hotel lost their lives.

This event highlights the precarious living situation for many residents in the city: the only affordable accommodation left is in increasingly dangerous historic rooming houses. It also raises the question: what will come next to the sizeable lot at the corner of Water and Abbot streets?

How will the broad interests, concerns, and perspectives of the various communities who live alongside each other, but often with very different life-worlds, be balanced in the future of this historic and contested neighbourhood?

About

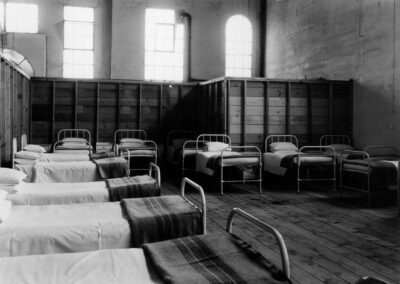

When the Winters Hotel was built in 1907 it was considered one of the finest hotels in Vancouver, furnished with the most modern amenities of its time including running hot water and telephones. The hotel was designed by William Tuff Whiteway (1856 – 1940), who also designed the nearby Woodward’s Department Store (1903) and the World (Sun) Tower (1912). Its listing on Canada’s Register of Historic Places notes “(t)he massive size of this structure illustrates the city’s rapid population growth at the time, and the increased pressure to accommodate seasonal workers at a time when the economy was booming”.

Viewed through the primacy of architecture, the Winters Hotels was B-listed on the City of Vancouver’s Heritage Register and “was valued as an excellent example of commercial design from the Edwardian era, demonstrating the local influence of the Chicago School”.

As we turn towards a vision of heritage that values multiple perspectives and seeks cultural redress with communities who have been excluded from the traditional approach, it is crucial to acknowledge that such population booms and economic growth also led to cultural erasure, territorial dispossession, and ecological devastation for local Indigenous communities. In our open letter about the Balmoral Hotel, we stated it is important not to distance ourselves from the present social context and history that led to today.

In recent years the Winters Hotel was a privately owned SRO, leased to a local housing non-profit organization and housing some of Vancouver’s most vulnerable residents on its upper three floors. Many of the residents of this hotel, including one of the victims who lost their life in the fire, are part of the urban Indigenous community who are both contending with the social outcomes of that ‘Edwardian boom’ while residing within its physical structures. The loss of the Winters Hotel is tragic for its loss of life and the sudden displacement of its survivors.

Context: A history of fire

SROs are often densely populated, aging structures in dire physical condition where fire has been a constant threat. It was anger over these conditions, and the lack of enforcement over fire, health, and safety standards by the state, that galvanized community activism into a powerful political articulation in the 1970s. In 1973 alone there were 107 reported fires and ten deaths, a tragic outcome that contributed to the founding of the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA). Fire in SROs, and community-driven responses to it, have been central to the neighbourhood’s larger fight for a right to safe, secure, and dignified housing.

Five decades on from DERA’s early campaigns, fire looms as an even more frequent threat to the homes, possessions, and lives of Vancouver’s most precariously housed residents and some of the city’s oldest buildings. According to The Tyee, Vancouver Fire Rescue Services responded to 312 fires at SRO buildings in 2021 and by September 2022 fires in rooming houses had become ‘a daily occurrence’.

In the case of the Winters Hotel, a previous fire three days prior to the one that would bring the building down had triggered the sprinkler systems and emptied fire extinguishers. These had not been reset or refilled before the deadly April 11 blaze. Drawing on Vancouver’s heritage of community activism and state responses in reaction to the dangerous state of our historic tenements, what would be an impactful outcome at the future of the Winters Hotel site?

What happens next?

The site of the Winters Hotel now sits fenced off, with City crews removing the debris of the demolished building. Scorch marks are visible on the neighbouring Gastown Hotel, another beleaguered SRO hotel with a long list of health and safety violations. The loss of the hotel has opened up a large lot for redevelopment at one of the most prominent intersections in Gastown protected ‘Historic Area 2’ (HA2), a location that has diverse and divergent meaning to many groups.

Based on other recent developments in the area, the scenario could involve the owner looking to assert their private property rights and maximize profitability; The City seeking to leverage social amenities from the developer in return for a relaxation of some HA2 by-laws; The business community seeking something that continues to press ‘history’ into the service of tourism and consumption; and the long-standing, low-income community hoping to retain homes, services, and a sense of place in the increasingly upscale streetscapes of Gastown.

How these broad interests are navigated remains to be seen, but a key feature of the City of Vancouver’s new Heritage Program (VHP) is a pledge to ‘support Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations’, and Urban Indigenous peoples’ self-expressed histories and heritage’.

The colonial narrative of the city’s founding, expressed through the monumentalization of its founder ‘Gassy Jack’, has long been represented as the official origin-story of Vancouver. The more recent ‘Beautification’ of the neighbourhood in the 1970s was underpinned by the cultural production of ‘Gastown’ as an urban birthplace. Whatever takes shape on this site needs to take all of this into account.

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia