The 800 Block on Granville Street, located between Smithe and Robson Streets and also known as Theatre Row, has been at the heart of Vancouver’s entertainment scene for a century now. Behind the façades of buildings such as the former Capitol Theatre (1921; later a multiplex cinema, and now gone), the Commodore Ballroom (1929) and the Orpheum (1927), movies were played, dances took place, and artists from all over the world have performed in many different forms and genres.

Outside, many claim, Granville Street lost its buzzing vibe. The introduction of the Entertainment District has been considered unsuccessful, and does not appeal to the multigenerational crowds that Granville Street used to attract many years ago. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing issues on this once thriving street in Vancouver. (Read more about the 800 Block on Granville Street in our 2021 Top10.)

About

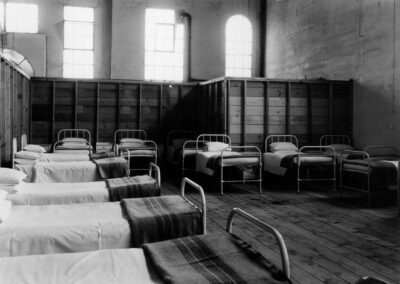

Already in the making for two decades, Bonnis Properties presented its first ambitious, yet controversial, development plan for the east side of the 800 Block on Granville Street in January 2021. Bonnis Properties owns most of the properties that are included in the plan, except for the building at the northeast corner of Granville and Smithe Streets and the adjacent, City-owned, Orpheum Theatre. The development site includes the Commodore Ballroom, the State Hotel built in 1910 (an SRO-hotel that has been vacant for at least 50 years), the Clancy Building (1913), the Cameron Block (1912) and the Service Building (1922), as well as three younger buildings.

The redevelopment proposal includes the complete conservation, plus interior updates, of the Commodore, and the preservation of the other heritage buildings’ façades, which would ensure that the so-called sawtooth character of the block is retained. Behind the facades and over the Commodore Ballroom, a terraced, 16-storey commercial building with office, retail and cultural space would be built.

Supported by the Downtown Vancouver BIA, the applicant claims that the proposal will revitalize the streetscape on Granville Street during the day and night, and will protect the “intangible and lived heritage” of the area as a music and entertainment centre from fading, while providing the opportunity for future generations to enjoy one of the most celebrated venues in the country, the Commodore Ballroom. Further, Bonnis Properties is willing to pay in lieu the $230,000 per SRO unit from the State Hotel, as per the SRO By-Law, if the density and massing of the proposal were to be approved.

Courtesy of Perkins & Will (https://perkinswill.com/project/800-granville/)

Why on the Top10?

The entire conservation of the Commodore Ballroom and interior updates can be considered a win for Vancouver’s cultural sector. Façadism (the preservation of façades) would retain much of the architectural-historical significance and appearance of the buildings, including the sawtooth character of Granville Street on this block.

However, the proposal does not comply with, and deviates considerably from, the five applicable policies and by-laws, including the Vancouver Heritage Program, Single Room Accommodation By-Law, Single Room Occupancy Revitalization Action Plan, the Downtown Official Development Plan, and Granville Street (Downtown South) Guidelines. An official application is not being processed yet, and the City of Vancouver sees the proposal as a test for staff in terms of creating a policy framework. Heritage staff have stressed that current Heritage Policy would not allow, and not encourage a potential application in this form. The developer argues that the policies are out of touch with today’s needs; City Council at the time seemed to not disagree. Canada’s Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places, a nation-wide acknowledged document that provides “sound, practical guidance to achieve good conservation practice”, requires new development to be compatible with, distinguishable from, and subordinate to the heritage place (Standard 11). Whether the proposed development meets these prerequisites largely depends on how the standard is interpreted.

From the Standards and Guidelines (Standard 11):

“[An addition or new construction] requires physical compatibility with the historic place. This includes using materials, assemblies and construction methods that are well suited to the existing materials.”

“[Standard 11] also requires that additions or new construction be visually compatible with, yet distinguishable from, the historic place. To accomplish this, an appropriate balance must be struck between mere imitation of the existing form and pointed contrast, thus complementing the historic place in a manner that respects its heritage value.”

“[Standard 11] also requires an addition to be subordinate to the historic place. This is best understood to mean that the addition must not detract from the historic place or impair its heritage value. Subordination is not a question of size; a small, ill-conceived addition could adversely affect an historic place more than a large, well-designed addition.”

Future

Heritage Vancouver Society remains involved in the discussion about these types of large development proposals in relation to heritage buildings. What will become of the 800 Block on Granville Street? What happens to the various layers of heritage on this block and for the future of heritage planning? What happens when there are questions both about its physical form and appearance and its intangible use?

Is it a win that façades are retained and the Commodore Ballroom’s future as a live music venue is ensured into some time in the future? Or is it a loss that built heritage conservation may only be able to come to fruition in return for large, new additions, and that other tools such as the transfer of density cannot be used? More importantly, in terms of new policy frameworks, what does successful heritage conservation mean?

The Standards and Guidelines were created to provide good conservation practice guidance for physical historic places; large blocks like 800 Granville do provide an important physical connection for people to maintain a sense of place. In a high growth city like Vancouver where density from developments pay for housing, public art, parks and other amenities, do these Standards and Guidelines matter for important historic places?

Photo by Ben Geisberg

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia