The Vancouver Heritage Register (formerly Vancouver Heritage Inventory) is a list of about 2,200 buildings and structures, streetscapes, landscape resources (parks and landscapes, trees, monuments, public works) and archaeological sites which are considered to have heritage value. The register was adopted by City Council in 1986, and has since been updated regularly.

The Vancouver Heritage Register is under review so it can be aligned with the Vancouver Heritage Program (2020), and for the City to be able to “identify, embrace and celebrate a broad range of places with social, cultural and historic values, based on principles of reconciliation, diversity and equity.”

About

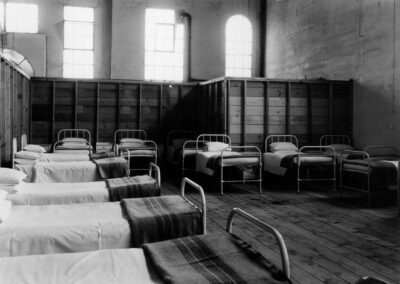

The Vancouver Heritage Inventory is the product of a time when heritage significance was determined by arbitrary grading systems, which find their origins in Europe and are strongly historic and aesthetic oriented. Various criteria are evaluated and ascribed a numerical score. The total score determines whether a building is considered to be of heritage significance or not. This type of heritage evaluation was introduced to Canada and the United States in the 1970s and still lies at the foundation of most governmental (municipal and provincial/territorial) heritage programs throughout Canada.

Vancouver’s first register for heritage places was the outcome of a windshield survey that identified more than 3000 “notable buildings” in the city (through additional research, it was determined whether the buildings should actually be considered for the register). The buildings, sites and objects that have since been enlisted on the register are subdivided in three categories:

“A” (represents the best examples of a style or a type of building, and may be associated with a significant person or event),

“B” (represents a good example of a particular style or type, individually or collectively),

or “C” (represents those buildings that contribute to the historic character of an area or streetscape).

If a place is municipally or provincially designated, it allows the City of Vancouver to regulate, by by-law, the demolition, relocation and alteration of the heritage place. When not designated, a building on the register can be unlisted, altered, and even be demolished.

The Vancouver Heritage Register is not unique to Canada, nor the rest of the world. Other Canadian cities such as Victoria, New Westminster and Toronto also make use of registers; the BC Register of Historic Places is the province’s official list of post-1846 historic places that have been formally recognized by the Province or by a local government.

On a national level, the Canadian Register of Historic Places is an online database of heritage places listed by one of the provinces or territories, and as such provides information, not protection. The United States has the National Register of Historic Places, managed by the National Park Service. World-wide, UNESCO promotes heritage places through a World Heritage List, Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage, and a list of Biosphere Reserves.

Constraints

The Vancouver Heritage Register is not only a planning tool through which change to heritage places is managed, it also provides information to the public about what has been officially recognized as “heritage.” As such, together with other heritage tools and policies, the register has shaped public understandings of heritage conservation, and of what heritage is about and what it is not about.

The City of Vancouver, heritage department:

“The Vancouver Heritage Register primarily reflects colonial, settler-oriented narratives of history which has perpetuated the erasure of the pre-existing histories and uninterrupted living heritage of Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations on unceded territory.”

Throughout the years, many voices have been excluded from conversations about heritage. The heritage register has contributed to this systemic problem by only recognizing heritage that takes shape in built forms, or objects. Until the general acceptance of values-based practice within the heritage field about ten to twenty years ago, enlisting on the register took place under the assumption that a place with heritage significance was considered to be of value for everybody.

As a product of its time, the heritage register was not designed to acknowledge practices such as weaving, food and language, and many other traditions that define a community’s identity. It was not designed to acknowledge the different layers of heritage, and the various meanings that can be ascribed to places and practices, both good and bad. It was designed to confirm and strengthen the notion of the settler-oriented narrative, and a traditional, Eurocentric idea of what heritage is.

Why on the Top10?

The City of Vancouver is currently revising the Vancouver Heritage Register as a list and as a planning tool. Preliminary research (Phase 1) has been finalized, and staff is now working on framework development (Phase 2) and content review (Phase 3) to align the register with the Vancouver Heritage Program. The outcomes of Phase 1 to 3 and implementation planning (Phase 4), as well as execution of the plan (Phase 5) are scheduled for 2023.

In terms of a particular approach to heritage (what can be called the historic-aesthetic bias), and a common understanding of property ownership and city planning (someone “owns” a heritage place and is restricted in making changes to it by City policies) the Vancouver Heritage Register is a useful planning tool that has proven to be successful in many occasions.

However, including heritage on a register is exclusive by nature. For many reasons, “all” forms of heritage cannot be acknowledged, and simply extending the register to cover heritage that has not been represented may prove difficult as the register system was intended for property. Also, acknowledging heritage on a formal list inevitably comes with the question: who decides whose heritage is recognized and protected?

HVS believes that a revised Vancouver Heritage Register alone cannot protect and support Vancouver’s many layers of heritage, and will have to be a part of a larger review of other, related planning tools and policies as well to create an environment in which diverse perspectives on, and expressions of, heritage can thrive.

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia