Increasingly in Vancouver, proposals that involve heritage buildings subsume them under much larger additions. You can see this with projects such as the (former) Main Post Office, The Bay, 800 Block Granville and First Baptist Church as part of the Butterfly.

The generally accepted idea by heritage professionals is that the heritage asset/building takes main consideration with the building addition being subordinate to it. With more and more projects, this may no longer be the case.

About

The rationale behind physical conservation is that the historic building has value to the public, whether historic, aesthetic, economic or cultural, or some combination thereof. That value is what is being conserved and is contained in the historic building. Therefore, the generally accepted idea with conservation is that the historic building remains the focus while allowing for change to it or around it.

Canada’s Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places, a nation-wide acknowledged document that provides “sound, practical guidance to achieve good conservation practice”, were created to provide good conservation practice guidance for physical historic places.

In particular, the most often cited standard in Vancouver is Standard 11. It requires new development to be compatible with, distinguishable from, and subordinate to the heritage place (Standard 11) to try and ensure the values remain present. Whether a development meets these prerequisites largely depends on how the standard is interpreted. Even though Standard 11 allows flexibility because it does not mandate technical specifications for size or form for example, adherence to the spirit of the standards is unlikely.

In a high growth city with high land values like Vancouver where density from developments is traded to pay for housing, public art, parks and other amenities, transactions that yield large, new additions on the site have become typical. Because designation and conservation of heritage buildings can and often require significant upgrades, restoration and compensation for loss of development potential (in general, keeping the current heritage building is usually less financially profitable because a higher building could be built on the site due to the zoning), built heritage conservation may only be achieved in exchange for a much larger building. The Butterfly/First Baptist Church (see p.5 in the link) project at Burrard and Nelson is a good example of this situation.

As reported in the Daily Hive:

Developed by Westbank, The Butterfly is providing one of Vancouver’s largest community amenity contribution (CACs) public benefit packages, as a condition of the project’s rezoning — worth roughly $100 million. This accounts for the social housing component, the in-kind value of $22 million for the seismic upgrade, renovation, and expansion of the 1911-built heritage church, and a $65 million cash contribution to the municipal government to support new and improved West End public amenities.

This is one reason that makes Standard 11 difficult to achieve.

Currently, the result is that the new addition in the project becomes the center showpiece and the historic building becomes the appendage that takes a lot of trouble to deal with. Another example is 800 Block Granville which we discuss in last year’s Top10 (in this case, the density is on top of the existing building rather than next to it).

Why on Top10

This has implications for built heritage conservation in Vancouver. As we pointed out last year when discussing 800 Granville, what does successful heritage conservation mean in Vancouver?

The focus of the Standard and Guidelines is to allow for change while trying to ensure good conservation practice to “guide decisions that will give historic places new life while protecting their heritage value.” It however does not have a focus on the financial context of land and development in cities like Vancouver where there is heavy reliance on transactions for social purposes. For instance, part of the proposed density/height for 800 Granville is to recover the $17 million dollars the developer would have to pay the City to replace social housing units on the site (there are 73 single-room occupancy units in the Slate Hotel building as part of the 800 Granville site).

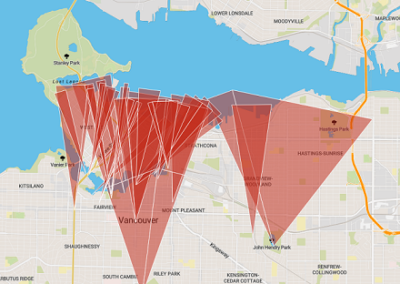

Under existing conditions of city-planning, heritage conservation is increasingly transactional – density transfers, revitalization agreements with restoration coming as a community amenity contribution in return for more profitable development conditions. For heritage conservation professionals, one of the more obvious solutions that come to mind is a density transfer where the allowable height is transferred to another site. However, Vancouver’s density transfer program appears to be on hold.

Are these transactions -and increasingly bigger and bigger transactions- simply an innovative tool for providing a public good or does it have adverse effects we need to consider when thinking about public goods?

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia