History hangs heavily over the Downtown Eastside. It is not just the old buildings which inculcate a sense of the past, far more powerfully, it is a place of shared sentiment and symbol, of collective memories – Shlomo Hasson and David Ley, 1994

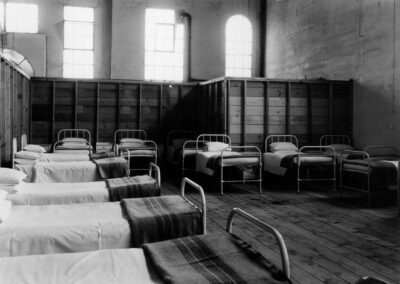

Throughout the dramatic economic and social transformations of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Hotel has retained a crucial, if beleaguered, role as the community’s last stop for housing. The SRO has become the definitive building typology associated with Vancouver’s oldest neighbourhood and the many contested strands of meaning that surround it.

With many of the hotels now approaching the end of their structural lifespan without major restoration efforts, it is likely that many more historic rooming houses will be redeveloped like the Stanley New Fountain, condemned like the Regent and Balmoral or tragically lost to fire like the Winters Hotel. There has been concern that the loss of so many SROs equates to the loss of a defining architectural character of the city, one that represents the rapid colonial settlement and growth of the city as a port and resource industry town at the turn of the 20th century.

But to highlight this historical and architectural perspective alone omits the lived experience of thousands of people who continue to live in these often dangerous and deteriorating structures. This could be viewed as privileging the past at the expense of the present. In our open letter on the Balmoral, we argued for a broader understanding of what these buildings represent to the community.

There are many people who have had terrible experiences in these hotels, and discussions about the future of these buildings should include the past and present social context around them and the people who have called them home. What do these places mean and will the community be best served by restoring or replacing them?

Historical context

The DTES is unique in Vancouver in many ways, not least because it is difficult to define in both its physical borders and within the civic imagination. It is the city’s oldest neighbourhood by official accounts, but even this is limited to colonial timekeeping. The sheer number of Indigenous place names that were subsumed under the street grid – Lek’ Leki (‘Beautiful Grove’ – Carral Street), Kiwah’esks (‘Separated Points’ – Main Street), K’emk’emelay (Grove of Big Maples – CRAB Park), and Skwachays (Deep Hole in the Bottom – East False Creek) hint at the rich linguistic and cultural heritage that inhabited the area before colonial displacement.

By the turn of the 20th century the DTES was an industrial and transportation hub and metropolitan extension of a vast resource industry. Residential hotels catering largely to loggers with various commercial outfits on the ground floor came to be the dominant form of architecture. A predominantly working class identity existed in these hotels alongside the upscale department stores, theatres, and office buildings of Hastings Street.

In the 1930s the area became a hotbed of labour unrest as the Depression kicked off a theme that would return to the area in various forms over the ensuing decades: political mobilization. The westward migration of the business district and decline of industry after WWII led to dramatic socio-economic decline, and the beginning of the ‘Skid Row’ framing that has come to dominate narratives of the area in some form ever since.

The complicated role of heritage in the DTES

The DTES’ relationship with heritage is complex and at times contradictory. During the urban renewal schemes of the 1960s – 70s, the actions of grassroots heritage organizations helped galvanize public opinion against ‘slum clearances’ and towards a policy of ‘rehabilitation’. These organizations have been credited with helping to save significant sections of the historic inner city from demolition.

But as these movements became more formalized and adopted into the city’s first Heritage Program, they also contributed to the fracturing of the neighbourhood into various sub-planning districts. The application of heritage protection accorded to selected areas (Gastown, Chinatown) led to aesthetic, social, and economic ‘revitalization’ while undesignated areas (the Hastings Street corridor) suffered from severe architectural deterioration, concentrated criminal activity, and commercial vacancy. Because of the considerable cost of restoration projects, such ‘upgrading’ activities require private investment and ongoing financial support from high end retail, residential, or business uses. Social services, including non-market housing, were concentrated into the ‘downgraded’, unrenovated, and undesignated sections of the neighbourhood.

The political spirit of those grassroots fights to save the neighbourhood never left after the battles over freeways and modernist towers ended. While architectural aspects of heritage were adopted as part of a wider economic development scheme from the 1970s, community advocacy also worked for social preservation in the face of growing threats to the community. If we think of heritage as a community’s ability to withstand displacement and remain in place, rather than saving an old building from being torn down, then the DTES has continuously fought to write its own story against the odds of political and real estate development pressure.

From Project 200, Expo 86, and Woodward’s to the ongoing struggles for safe, dignified, and accessible housing, the residents of the DTES have created a political culture where their right to remain has been entrenched in Vancouver’s current ‘revitalization without displacement’ strategy.

What happens next?

The recent civic strategy to address the many complex and overlapping social challenges in the DTES includes publicly acquiring the remaining privately owned SRO hotels for restoration or replacement. There is also a stated goal to disperse social housing throughout the city and region. In the DTES, low-income housing will be improved but numbers will be capped, while a significant increase in market housing will be added into the area.

In assessing heritage concerns about the area, we suggest balancing the call to protect buildings on the heritage register with a consideration for what will improve the lives of the people who live or have lived within them.

We are conscious of the shared histories and material experiences that make a neighbourhood, and that architectural preservation should not come through disadvantaging the vulnerable populations in the DTES or displacement. If new facilities will help the existing community to heal, remain, and thrive, that sort of social preservation should be valued alongside physical markers of the past.

References

Blomley, Nicholas. 2004. Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property. New York and London: Routledge

Hasson, Shlomo, and David Ley. 1994. Neighbourhood Organizations and the Welfare State. Toronto : University of Toronto Press

Smith, Heather A. 2003. “Planning, Policy and Polarisation in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 94 (4): 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00276.

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia