About

The closure of Hudson’s Bay Company’s downtown Vancouver store marks the end of a major chapter in Canadian retail history. Recently listed for sale by CBRE Investment Management, the uncertain future of this landmark building raises questions about historic building preservation, downtown vitality, and the difficult, shared history between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The Hudson’s Bay building at Granville and Georgia is one of Vancouver’s most significant heritage structures. For generations, it has served as:

- A major downtown anchor and gathering place

- A symbol of early 20th-century department store architecture

- A marker of Vancouver’s emergence as a regional commercial centre

- A physical reminder of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s role in shaping Canada

Its closure reflects broader shifts in retail, downtown foot traffic, and the decline of department stores nationwide. The loss of such an anchor tenant has implications not only for the building itself, but for surrounding businesses and the economic health of downtown Vancouver. Beyond the building, it is critical to reflect on the Hudson’s Bay Company’s part in the colonization of Canada and the enormous impact it had on Indigenous peoples, especially as news of the Bay’s historic artifacts have been receiving media attention.

The Vancouver Building

The downtown Vancouver store opened in Gastown in 1887 before relocating to its current site at Granville and Georgia in 1893. Over the next several decades, the building expanded in stages, reaching its present form by 1927. Designed as a grand department store, it functioned not only as a retail space but as a social destination with restaurants, dining rooms, and multiple specialty departments.

Architecturally, the building is distinguished by its terra-cotta façade, Corinthian columns, decorative coats of arms, and monumental scale. For nearly a century, it has been a defining presence at one of Vancouver’s most prominent intersections.

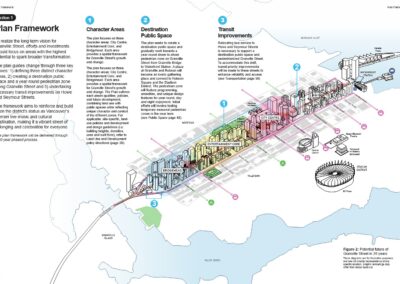

The building is currently listed for sale by court-appointed receivers, with major brokerage firms acting as advisors for prospective buyers. The 600,000+ sq ft property occupies one of Vancouver’s most prominent downtown intersections, with direct subway access and proximity to major retail and office corridors.

Previous redevelopment proposals envisioned a dramatic intensification of the site, including a large office tower addition above the heritage structure and extensive interior demolition. While those plans may now be revised due to market conditions, the core tension remains: how to adapt a large, historic department store for contemporary uses without eroding its heritage value. Much of the public discussion to date has focused on the monetary value of the property, office space, condos, hotel potential—while less attention has been paid to the cultural, social, and heritage implications of redevelopment.

The building’s heritage designation offers some protection against large-scale exterior alteration, but it is not absolute. Heritage protections can be amended or weakened, and interior heritage value has already been compromised by decades of renovations.

Experts note that while adaptive reuse is possible, it will require major investment, technical care, and a commitment to retaining key heritage features. Without that commitment, there is a risk of façade-only preservation.

Why on Top10

The Hudson’s Bay building is not just a relic of retail history. It is a symbol of Vancouver’s growth, Canada’s colonial economy, and a shared and difficult past. Its future redevelopment will signal how Vancouver values the different aspects of heritage in moments of transition: whether landmarks are treated as obstacles to be overcome, or as opportunities for deeper reflection, stewardship, and dialogue.

Beyond Architecture: Shared Histories

The Hudson’s Bay Company occupies an unique and fraught place in Canadian history. Established in 1670 through a Royal Charter, it played a pivotal role in shaping Canada’s history and its relationship with Indigenous Peoples. The Charter granted Hudson’s Bay Company control over vast lands draining into Hudson Bay—about one-third of present-day Canada—without recognizing the sovereignty of the Indigenous Nations already living there. The Charter did not simply create a company, it functioned as a form of colonial governance and treated the land as a commercial asset.

As a result, Hudson’s Bay buildings across Canada are not just commercial landmarks; they are physical reminders of a shared history between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, one shaped by trade, dispossession, treaties, and survival.

One perspective on this was expressed by former Nunavut premier Madeleine Redfern in parliamentary testimony regarding heritage:

“Protecting even the Hudson’s Bay Company building in Winnipeg is incredibly important to Indigenous people… because the history of that particular company involves almost every Indigenous community across the country. We want to see our history included in those stories, not just the perspective of the company.”

This perspective underscores an important point: there is more than one point of view and more than one aspect when the word heritage is used. The heritage interpretation of Hudson’s Bay buildings cannot be limited to the buildings themselves and cannot be limited to settler or corporate narratives alone.

Elsewhere in Canada, the future of former Hudson’s Bay buildings has prompted new conversations about reconciliation, heritage, and adaptive reuse. The transformation of the Winnipeg Bay building under Indigenous ownership has been cited as an example of how the complexity of such sites can be reimagined.

How Indigenous histories connected to Hudson’s Bay are acknowledged or engaged, how redevelopment proposals effectively address the multiple aspects of the building’s heritage values and meanings, and what will happen to downtown cultural life, are all of interest when thinking of this building.

Additional Resources

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/hudsons-bay-vancouver-1.7496684

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia