Shaping Vancouver 2019: Conversation 1

What's the use of heritage?: Re-shaping local communitiesMay 21, 2019

In this session of Shaping Vancouver, we look at how heritage can be used to reshape particular places in the city. In particular, we examine how culture-led plans can fulfill economic, social and cultural objectives set for areas such as Chinatown and Punjabi Market.

Moderator

Bill Yuen:

- Executive Director of the Heritage Vancouver Society

Panelists

Ajay Puri – Community organizer

Alisha Masongsong – Project Manager, Exchange Inner City

Belle Cheung – Social and Cultural Planner, City of Vancouver Chinatown Transformation Team

Elia Kirby – President of the Arts Factory Society at 281 Industrial Avenue

View a recording of the talk above. The video is part of a playlist – there are eight parts in total. Clicking on the play button on the YouTube video above will start the playlist, which will auto-play the entire talk’s playlist. Navigate through the eight parts using the sidebar of the YouTube players.

Under many different names, including “revitalization”and “regeneration”, heritage is and can be used to craft a positive place image, develop local economic sectors, create a neighbourhood centre for culture, and improve upon the animation of local areas. This change can be compelling, but also has its challenges.

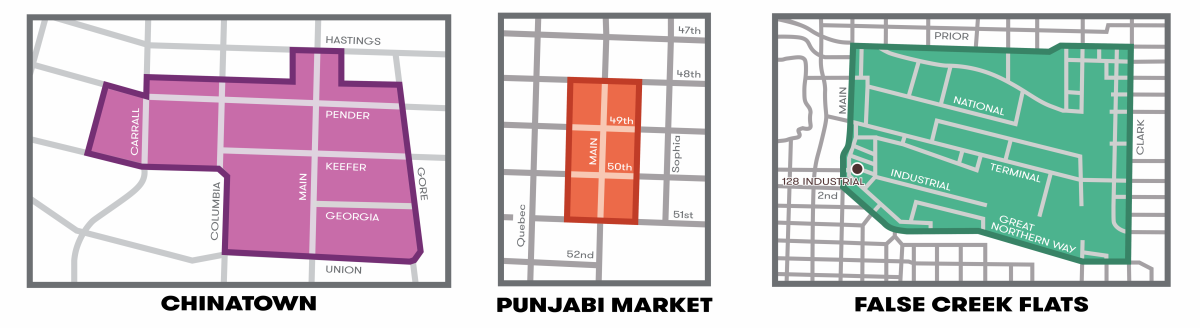

This process is especially relevant and timely in the False Creek Flats, Chinatown, and Punjabi Market areas of Vancouver. Under the False Creek Flats Plan approved in 2017, the approach is to make the area a thriving and innovative economic zone which “builds off of existing character… by leveraging key character assets, histories and economic anchors”. Chinatown is looking towards a process (including application for World Heritage) where a heritage informed by experiential authenticity, culture and ordinary daily life forms the basis for social and economic revitalization. Punjabi Market, while not having undergone extensive planning exercises, desires a future where the three block district is a place filled with South Asian experiences for people to enjoy.

Introductions

Moderator Bill Yuen started the conversation by introducing the topic of the talk and discussing how heritage can be used in ways beyond its common conception as a way to save buildings. Bill emphasized the place of heritage within the context of the City of Vancouver’s upcoming city-wide plan and the need to make heritage relevant as well as demands for new approaches to heritage. He also talked about the shift from viewing heritage as an object-focused way of thinking to a landscape-focused way of thinking, which is crucial for looking at how heritage relates to and integrates with reshaping local areas. Landscape-focused heritage views heritage as an ecosystem where one thing affects everything else, whereas object-focused heritage tends to view singular objects in isolation. Heritage is traditionally very site-focused and Bill emphasized the need to include a holistic approach as well. A very important distinction between object-focused heritage and landscape-focused heritage is that object-focused heritage tends to be the realm of architects and historians and landscape-focused heritage tends to be the realm of those who use an area.

Next, the panelists each gave some introductory remarks.

Elia Kirby is President of the Arts Factory Society at 281 Industrial Avenue, which is an arts hub that supports artists in False Creek Flats. Historically there’s a large population of artists, arts organizations, and studios in False Creek Flats. This has occurred largely because of “the concentration of industrial land which happens to exist there”, and how a lot of artists gravitated to that area because it was accessible and affordable before becoming a cultural magnet for more artists to follow. One of the things that is happening right now is a large amount of gentrification and redevelopment and the pressures that are being put on this area is starting to really threaten that community throughout. The Arts Factory communicates that and is raising awareness about how the artists are contributing to the community and maintain economic and social activity.

Belle Cheung, a social and cultural planner from the City of Vancouver, described Chinatown as an area that “needs no introduction” but is also a place that stands for and represents a lot of the city’s history which, until very recently, has not been discussed. Chinatown’s identity lies in its “history and its cultural heritage” as well as the way of life it represents- migration to Canada. Vancouver’s Chinatown is also unique in that it is one of very few North American Chinatowns which has not had to move from its original location east of downtown. Belle also emphasized the connection that Chinatown’s history of racism and oppression has to other non-white communities across Canada.

Ajay Puri, a community organizer based in Punjabi Market, questioned what values the city has and who it is for. This question rings very true with the community in Punjabi Market. He introduced the area by discussing its relative obscurity today and decline over the past two decades as more and more Punjabi and Indian businesses move to Surrey and other areas of the Lower Mainland. An example was brought up in a new development on the corner of Main and 49th, where a local coffee shop is heavily impacted by a new Tim Hortons that opened across the street. He highlighted the role of people to honour and preserve the past as well as bring it into a recognizable future where people can live, work, play, and learn from each other.

Alisha Masongong introduced her area of work with Exchange Inner City in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) and other inner city neighbourhoods. The DTES “is known as one of the poorest postal codes in Canada” yet is a rich community with people from diverse backgrounds and resources. The heritage values seen in the DTES are in shops and places like the Carnegie Community Centre and Ovaltine Café which serve the community with open spaces and services.

Questions to the panelists

We talk a lot about using heritage to reshape local place, and now it’s in a planning document (the False Creek Flats Plan). Do you derive much comfort and feel secured and strengthened by that?

Elia opened by looking at the evolving shape and form of communities and life in Vancouver in the context of the arts, talking about how the arts have been pushed into smaller communities, with the loss of artist studios being particularly notable. Artists are increasingly moving out of the city. One of the things that the community is struggling with right now is the current City Council, which has an intense focus on housing.

While grateful for that focus, and for having the community be noticed and codified, Elia noted how some citizens are concerned that the loss of industrial space and its associated decline in cultural activity as new high-rises are put in. The importance of networking and working with other business owners was noted, as well as the challenges of working with the shared artist space. Elia said it can be tricky to recognize artists because they are a less well-defined community, but they are nevertheless important contributors to the spirit of the city as content-creators. To Elia, high-rises are not looked at with pride in the same way that the public art is, which he sees as the city’s legacy.

The Punjabi Market is also in the Sunset Community Plan. Can you tell us about the report that you worked on and how it relates to the Plan? (27:15)

Ajay talked about how he was commissioned to work with local partners by the City of Vancouver in response to an open forum they had for development regarding the area around Main and 49th Street to determine what the community would like to see on the corner. Ajay worked directly to foster connections and consultations that allowed the City to carry out a retail analysis study and survey the area for what would best fit future development. They worked on that report for about a year and a half, an experience that was enlightening and engaged; through the process, he discovered how distant the city actually was from Punjabi Market. Ajay also discovered widespread apathy from Punjabi Market business owners, who have a lot to say about the neighbourhood’s future but have grown to distrust the City because they feel like their comments will not matter. While once there were 300 shops operating in Punjabi Market, today roughly a third of the storefront are empty. In the end, Ajay discovered that both the City and Punjabi Market locals wanted to work with and help each other but were at odds in their methods and execution of carrying out plans or ideas. Ajay emphasized how the report outlines “what’s happening in the neighbourhood here’s what people want”, and allows both parties to move in unison. Since the City has heard the report, they have moved ahead with a 5-year management plan regarding the tangible and intangible assets of the Punjabi Market community. Ajay also talked about the community’s wisdom council and the importance of the elders in the community in the process of looking towards the future of the area. Ajay looks at Punjabi Market’s experience as showing the possibilities and successes of citizen power and the neighbourhood’s function as a case study for future acts of engagement and constructive city planning. The core of his idea is to have everyone see Punjabi Market as a vibrant community of people, food, shops, and ideas, and to approach it in that way.

Chinatown is undergoing some planning work around basing the planning on culture as opposed to residential intensification. Belle, can you talk to us about how you’re using the terms ‘living heritage’ and ‘intangible heritage’ to shape the neighbourhood and how that may be applicable to other neighbourhoods around the city? (33:30)

Belle said that the team is, in fact, trying to move away from those terms since they are not good for talking about what is important to the community and are difficult for the public to understand. Up to now, much of the heritage focus has been on buildings and the physical structures whereas the focus is trying to be shifted more towards intangible heritage, which “really is everything that happens within those spaces”; in this context, the stories and interactions that take place inside these buildings define and shape what the community means to people. She encourages people to use the terms “intangible heritage” and “tangible heritage” together to fully encompass the meaning and feeling of Chinatown. Examples of this overlap include the Chinese New Year Parade, narrow storefronts with neon signs, milk tea at local bakeries, eating Dim Sum, or connections that people make within kin-based organizations. These are all examples of how intangible and tangible heritage are inextricably related and essential to identifying and discussing heritage values and the importance of heritage in Chinatown.

Ajay added on to Belle’s discussion of tangible/intangible heritage by pointing out the importance of living heritage; people “don’t want a museum” and it is important that living history is kept alive and around. Although events or aspects of heritage don’t have to continue for decades in the exact same form, it is important that heritage is kept active so that new generations are able to get excited about intangible heritage to organically continue traditions. Vibrant neighbourhoods such as Chinatown and Punjabi Market cannot be “ghost towns or old history in a museum”. Finally, Bill mentioned that heritage “goes beyond ethnic and cultural traditions” are the sharing of space and development of interpersonal connections between groups are also important.

Could you explain what a Community Benefit Agreement is and why the people you are working with are seeking this agreement? (40:30)

Alisha talked about how the Community Benefit Agreement (CBA) policy (a legally binding contract regarding the development of a building/project that is negotiated between the development group, the City, and various stakeholders) was passed by the previous City Council in October 2018 and is working to be implemented by the current Council. Any building over 4,500 square metres must go through a community benefit process which mandates that the development group needs to meet a minimum target of 10% local hiring, as well as 10% local procurement of goods and services, through all phases of a development project. The CBA is in place not just for the planning and construction phases of the building but through the building’s lifespan as well. The CBA, which can be reviewed and updated, allows for the building to adapt to local and environmental needs, to maintain heritage and cultural assets, as well as build capacity for local, social enterprises and small businesses. St. Paul’s Hospital is a location where a CBA was recently passed. Parq Vancouver, Olympic Village, and Hastings Racetrack are big developments where a CBA was trialled and tested.

Bill then asked about what the process of planning and carrying out a CBA is like (45:00), leading Alisha to also talk about Community Amenity Contributions (CAC), which function like voluntary versions of a CBA policy but on a smaller scale. A CAC is mostly a conversation between the developer and the City to decide what is best for the community, and requires developers to provide specific community services in return for the right to develop more or higher buildings. With a CBA, on the other hand, the community has more of a say in the conversation, and the benefits to the community are actually written in to the development contract. An example of a CBA could be that a developer is required to hire a certain percentage of their workforce from within the community, or get a certain percentage of their materials from businesses in the neighbourhood, in order to ensure that the community actually sees some of the benefits and money generated from developments in their neighbourhood. In the Downtown Eastside, CBAs can be used as platforms for more workforce development and diversification as well as training to ensure that social enterprise groups have access to the services and that the developers are building.

Elia added in that, in the process of community development, the community needs to be the developers in the room as opposed to just stakeholders or contracted from the developer. Small-scale development is beneficial but is hard to do, primarily due to lack of access to capital. Elia advocated for City to conduct more community engagement in the development process itself, which Alisha talked about as part of working groups which the city organizes to engage with community members to discuss new opportunities in development.

Finally, Ajay (51:40) discussed community engagement in the broader context of transition and how important community engagement is. He emphasized the importance of having locals, both old and new, meet, talk and become integral parts of planning and development processes. However, he also brought up the examples of a proposed India Gate and the naming of the Langara-49th SkyTrain stop as instances where sharing of power failed due to one side not holding up their end. Working with various partners, especially on a large scale, requires successful and efficient power-sharing and accountability to create a community and space for everyone.

How can unremarkable spaces be important for their use, especially regarding the artists space at 128 Industrial Avenue? (57:00)

Elia started by discussing old buildings as decaying logs, which provide important space and shelter for the surrounding people and communities. He talked about attending a community engagement process and learning that the area around his building would be zoned as an “Innovation Hub”. However, this was a small victory in preserving the Arts Factory and False Creek Flats because the larger area plan was completely different and the character of the area was to be erased. It was to go from single story warehouses to five story buildings with non-market residences on the top two floors. Elia described the frustration of working to preserve his building at 128 Industrial Avenue and the hard work that went in just to learn that the building was going to be torn down anyway, despite low turnover rates of tenants and large community activism. These old buildings are important because they are the most accessible spaces for young people, minorities, artists, and emerging businesses. According to Elia, there is high demand for space in 128 Industrial Avenue. He does not trust the City because the City will not tell him rent amounts for a new equivalent space like they promised, or how the move will be facilitated as it will undoubtedly cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. The spaces protect these people and allow them to grow so that they can contribute to and become part of the city.

Belle chimed in to comment on the relevance of affordability and accessibility, echoing Elia’s sentiment regarding how, without people occupying a space, a building it just four walls. In Chinatown, there is a move to centre conversation on what happens in the spaces since the inherent value of the building is already known. Currently, some buildings are quite valuable because of their uses but their heritage value is not easily assessable because their buildings are not particularly unique. The Sun Wah Centre at 268 Keefer in Chinatown, for example, is a former shopping mall that is an important place due to its current use rather than for its aesthetic–today the Centre houses a contemporary Asian art gallery, a number of artists studios, and office space for a wide variety of non-profit organizations.

Questions from the audience

Question 1 (1:13:30)

An architect and False Creek South resident that works with RePlan*, asked about the economic basis that created the spaces that the panelists’ communities are in. These communities, particularly Chinatown and the area around Main and 49th, used to be much more affordable than they are now; the current market paradigm does not support these spaces easily or affordably. He referred to Elia’s discussion of non-market solutions and trusts as models for dealing with the evolving economic reality. This was the basis for a question about how these communities can deal with this evolving economic landscape.

Elia talked about how there are financial tools to deal with those issues but are not available in British Columbia. In the meantime, Elia advocated for the alternative of long-term leases, as you can get a mortgage on a long-term lease, and advocating the City of Vancouver for accessible rates, seeing as the City itself is the largest landowner in Vancouver. Much of the impetus for this action lies within existent community groups and non-profits.

Belle (1:13:30) talked about how the City is under review of its employment lands and how there is a 30 year focus about what can be done with those employment lands, especially the industrial areas around Strathcona and False Creek Flats. She also encouraged people to engage directly with City staff at places like public engagement sessions to advocate for specific needs and changes that people would like to see reflected in the city (such as maintaining buildings with cultural assets or that are of value). Ultimately, both panelists emphasized the need for community organization and the need to talk directly to City staff and Council members.

Question 2 (1:15:30)

An urban planner and community organizer posed a question for Belle regarding the relationship between intangible heritage and people. He brought up how Chinatown is stuck between building a living community or a museum which protects heritage (i.e. everyone thinks that bike lanes are great, but they are associated with trends that bring ‘hipsters’ into a neighbourhood and are can displace residents. Do we install bike lanes to improve the community or do we refrain from installing them to protect ward off displacing influences). He asked specifically how a heritage framework and its associated tools can be used to protect long-time residents.

Belle stated that what the City is trying to do in Chinatown is to make heritage about people. Currently, the City is mapping cultural assets in Chinatown to create an inventory of everything that is valuable to the community, including stories, food, festivals, etc., with the goal of putting an emphasis on how to understand Chinatown as a place. The Cultural Asset Heritage Management Plan, as it’s called, comes with the long-term goal of assessing what is of value to locals and to make intangible heritage a part of the city’s approach to the community.

Question 3 (1:25:20)

Are there other transformation teams assigned to other areas of Vancouver? If yes, what are they? If no, will it be part of the citywide plan?

Belle stated that currently, Chinatown is the only team structured although there are other neighbourhoods in similar situations and circumstances. However, she emphasized that her team is a model for preserving heritage in other neighbourhoods–especially racialized communities–in Vancouver. A unique aspect of the Chinatown team is how the team “looks like the people we’re helping” and is fully integrated into the community.

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia. Thank you to SFU’s Vancity Office of Community Engagement for co-presenting the series.

All photo credits go to roaming-the-planet.