Our Living City: Chinatown's Mon Keang School and the Next Great Save 2024

We talked with Jeffrey Wong, Vice President of the Wong’s Benevolent Association in Chinatown about the Mon Keang School building. At the time of writing, the Mon Keang school building is competing alongside finalists across the country in the National Trust’s 2024 Next Great Save, vying for up to $50,000 to put to saving or renewing their historic place. The competition is done through voting by the public. The National Site’s page for Mon Keang School describes it as a very holistic heritage place:

…established in Vancouver’s Chinatown in 1925 at the peak of the Chinese Exclusion Act and its racial discrimination. The School uses cultural language learning to anchor family relationships, strengthen community bonds, and build the local economy of Chinatown. As a building situated at the heart of Chinatown, Mon Keang is more than just a place for a community-based language school, but also a space that offers intergenerational social gatherings and cultural teachings.

Disclaimer: The views expressed below belong to those being interviewed and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Heritage Vancouver.

Thank you to Ausra Valickaite and Leticia Sanchez for helping with this article.

All images provided by the Wong’s Benevolent Association.

What’s the name of the building? Is there an official name? I’ve seen different names.

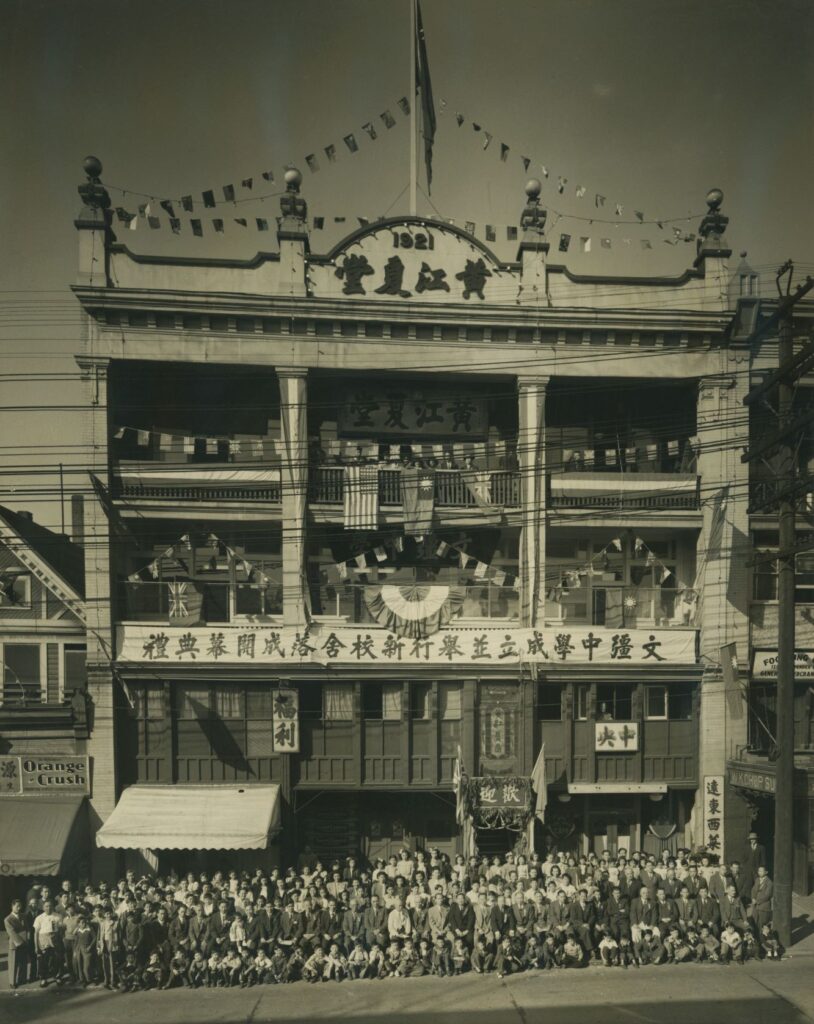

There’s no official name but the original name of the building was the Wong Kong Ha Tong. But in 1970, the Wongs consolidated their two associations and they founded the Wong’s Benevolent Association. So, we’ve since been calling it the Wong’s Benevolent Association. But the building also houses Mon Keang School. And Mon Keang School is the more outward facing organization. So, a lot of people lovingly nicknamed the building, the Mon Keang School building.

Where did the name come from?

Mon Keang School was named after the Wongs’ ancestor Mon Keang. Our founding members decided to name the school that because Mon Keang was famous in China as one of the most famous filial Sons. And so they want the future descendants, the future students of the school to be just as filial and just as smart in their upbringing. Mon Keang means strong culture.

For background, can you talk about the idea of a society building?

The Wongs in Vancouver actually were around since 1910. The original headquarters was in Victoria, but as the population in Vancouver grew, the Wongs in Vancouver decided they actually needed a space. Especially when Chinese exclusion was on their tails. So, in 1921, the Wongs, in Vancouver, decided to fundraise to, to buy this building and to actually build an association specifically for the Wongs. So in 1925, they actually were successful and then the building was opened. And they converted a two-story building to a four-story building with the intention that the Wongs were going to have to provide for their members, with legal aid, job opportunities, and most importantly charity work and specifically regarding educating the youth in the neighborhood.

So the children at that time were very rare, there’s not a lot of families in Chinatown at that time because women weren’t allowed to come to Canada. It was mostly a bachelor society. So by 1925, they realized that at any moment the government might kick the Chinese people out of the country. And so, the children will need to return home back to China and function in that society. So, they really, really focused on their Chinese education. There was also a need for education in Chinese because job opportunities that weren’t outside of Chinatown were very few. And so, when you work in Chinatown you need to know how to read and write Chinese as well. So, they really, really focused on teaching their descendants Chinese. But as the Chinese community began to grow, they realized that our association should look beyond the Wongs. And so they opened the membership and the school to non-Wongs and anyone in the community could come as well. And since then, there’s been thousands of students. 3000 students roughly graduated from the school. In 1947, they also expanded the school from one classroom up on our fourth floor in the hall, to a full floor with five classrooms on the third floor.

So the school, was it only a Cantonese school or did they teach other things?

It was predominantly run in Cantonese. But they also had a math class, geography, history and a kind of social studies. At that time our school was actually one of the four founding members of the Chinese education board and the four schools got together and decided what was important to teach the students.

Right. So why is Cantonese such an important part of the school historically? And then now?

Yeah, historically Cantonese was the language that the immigrants, Southern Chinese people, spoke. They might have spoken in a specific dialect but Cantonese kind of incorporates all of it and it kind of works and flows together. It was very important because the main population in Chinatown at that time only spoke Cantonese or some kind of dialect on the same lines of Cantonese. To teach them Cantonese was to kind of help them understand what the neighborhood was going through, and to be able to function in the neighborhood.

Nowaday it’s very important because a lot of people still speak Cantonese in Chinatown especially, especially the older folks. If you say we should move on to another type of Chinese dialect, you are kind of forgetting those that are still in Chinatown and actually might need it the most to be able to communicate. And so to preserve the language is actually to preserve those services in Chinatown and also to kind of keep the culture alive.

You have different students from different backgrounds who come to study Cantonese nowadays, right? Why are they coming to study Cantonese?

Because they want to connect with their culture. Either they never learned it as a child or they’ve forgotten it. I could give an example about myself. It was around high school I actually kind of lost my Cantonese a little bit. It’s because in Canadian society growing up it’s like, oh I can speak English and it’s the easiest way forward and uh, all my friends speak English. You kind of want to reach out to your family or your culture again and so you want to relearn it. When I grew up, I wanted to connect with my elders but all of them did not speak English. So, trying to speak with them in Cantonese was very difficult at that time. So going to these schools,it’s a way to kind of connect with one’s culture and learn some of the practices our elders have passed on to us.

I also know that you have students who don’t have a Chinese background, right? Why are they interested in learning Cantonese?

There could be many reasons. It could be because they have family or friends or their partner or their partner’s family that can only speak Cantonese and they want to connect with them. Or they’re really, really passionate about the neighborhoods or Chinatown, which are still predominantly speaking in Cantonese. And they want to frequent the shops and businesses that are owned and run by owners that might not speak English or they want to kind of understand what some of these stores or these restaurants are selling. They want to learn and engage with some of these businesses.

What do you see is the role of your building in Chinatown?

There is heritage and the culture, the archives, and the history that has been here for centuries. And so that’s very important. But at the same time, the building is not a stagnant museum. It’s not just about old archives and old stuff. There’s still a lot of seniors that come in day-to-day to practice their culture without even knowing they do it. It’s a hangout space for the Wongs, get the news of the day, understand what the association is going through, kind of hearing about what’s going on in the community, it’s kind of like a social services at the same time where sometimes a senior will come in and they need help filing their taxes or reading a letter so there’ll be people there to help. We still operate the school with a newer program, it’s still teaching Cantonese and is still trying to teach the culture. So I see it more like a living museum or living heritage, where people can come in and out and learn the culture, and learn the practices.

You mentioned you have archives there. You have all these records and like documents and photos stored in the building? Or is it presented?

It’s stored in the building. So, we have about a hundred years, so ever since since we found it and even a little bit before we found it. In the 90s some of the elders saw an importance in displaying some of their history. So, they created an archive group to display all their old photos and documents. Um, but then later on when I got involved, I kind of convinced them that they needed to digitize it and preserve it as well, and not just display it on a wall. We’ve been kind of archiving slowly, categorizing and digitizing and then displaying some of the things that we find. Like okay, we could display this without worrying that the building’s condition might ruin it or something like that.

What is your relationship to the building? You’re a Wong. Do you have an official position?

I got involved because I was interested in history. I was writing a paper and then I went up to the Wongs and I just fell in love with the place. And I didn’t understand what Chinatown Clan Associations were about. To be quite honest, I didn’t even care. Like, oh, I was a Wong, what does that even mean, right? But I got involved with the association and found out about the kinship that was always there, and the historical context of why these clans were founded: to protect one another, to help one another, to provide services for one another. But the Wongs also provided services for the community. So it became a real passion of mine to continue their legacy. Slowly, I went from a volunteer to a director to now Vice President to help oversee some of the operations. We own the building so we have to ensure that the building is still in good enough condition so that Mon Keang school and Hon Hsing athletic club is operational in these spaces.

You are in the documentary Big Fight in Little Chinatown. You have a part and you talk about the weight of the ancestors, is that right? Could you talk about that weight? I imagine it is not easy to be a steward of this building? What are some of the things that you encounter that make it really hard?

We have to ensure that these places are still standing for another 100 years. Because my elders have always taught me that the association was founded under such harsh conditions, under exclusion, and the great depression was right around the corner. So if we were able to hold on to this place and keep it running for so many years, a hundred years now, if we drop the ball, it’s a shame. It’s like a complete shame. And we lose the legacy that they wanted to provide for the community. We lose a huge chunk of culture and what they wanted to pass down to their descendants, to our descendants. So, I see that my job is to make sure that these places remain standing for another hundred years so that the culture and building can remain and still be passed on.

The problems with the building never cease to end because it is a hundred year building right? So, all the ancestors are upstairs on the fourth floor. There are photos and there is a large photo with all the past directors and all the members, there is a portrait of Mon Keang and our mythical ancestors. They are on the fourth floor and we constantly have to work and think about them, right? So they don’t come crashing down on us. The building is their house.

Is the physical maintenance and upkeep one of the hardest parts of your job as vice president?

Yeah, that is the hardest part because we are all volunteers. We have a directorship of twentyish directors and a lot of them are seniors, so they do not really understand construction and contracting and what not, but the new directors we are all volunteers with different backgrounds but none of us are really experts in heritage building preservation. My passion is history and archives, but most of the time my energy is pulled to figuring out how to fix the roof or repair a window, that kind of stuff a lot of our energy is actually pulled into things that we are not really certain of.

When Steven Quinn interviewed you on CBC about the contest, I think he said something to the effect that he didn’t think the building was an architectural marvel. What did you think when you heard that?

I think everyone has their own opinion on what is impressive or not, to me in Chinatown I find our building is quite impressive. It is unique, but its not just about aesthetics or the visual,. The building is nice on its own but it also has all this historical context that comes with it. The building was built by the Wongs in 1925. There is all these meanings that they wanted to project with this building, ah, so the recessed balcony is to harken back to their hometown in China. All the Wong’s, all the southern Chinese houses had these recessed balconies, so it is very historic. Ah, the building itself, interior wise, and the fixtures was not typical, it was extremely modern. It might look really old in history right now, but back in 1925, it was the most expensive, it was the most modern thing the Wongs could have bought at that time, and it was the meaning for the Wongs to project modernity. China, at that time, had just switched over 1911 had just switched over from the dynastic period and they wanted to project themselves in the world as a modern country and great power, so the Wongs wanted to take the lead and also project it in a Western country, They were Chinese people in Canada, and so they wanted to have this image that the Chinese are also modern and not just your typical, stereotypical Chinese, at that time, opium smokers or gambling den owner which is completely banned in our association at that time as well. There might have been a Chinese altar to our ancestors, but that is basically it; the rest is all modern, modern Western construction ideals, and so, that is what is missing when you just look at it from face value.

Is there a spot in the building that has important connections for you?

The hall is quite a gem. The hall is, again, all original: all the chairs and the tables, the altar, then even the wall hangings, the paintings and portraits and the mirrors are all original to when they bought the building in 1925. It was all member-funded, so all these immigrants, immigrant labourers that made a dollar or two a month, donated money to help buy everything in this association. So it is quite touching to think that they actually were able to get together and found this association. The great depression was a couple of years down the road, but life was not easy, and for them to buy this basically a mansion when all of them worked maybe at a grocery store, at a farm, as a house boy. Seeing Western people live in these mansions, some of them that had worked as house boys, by creating this association, it was a little touch for themselves to have this kind of wealth, right, to consolidate their powers to have strength to protect each other.

So the hall kind of reminds me of them every time when I walk in and all the events that took place since then. The school itself, it’s also quite interesting to think that of how many alumnae came through the space, hundreds of thousands of alumnae that came to the space and all these children and how active the building was and the potential that it can still be like.

On the page for the contest for the National Trust, you talk about how you are going to use the money or some of the things you may use the money for, but you also mentioned the sort of specific aesthetic you are trying to conform to. Have there been issues with that?

The elders have made minor tweaks to the building, so they had made modern improvements, to say, to some of the windows using vinyl windows in the back, and it was a lesson for us young people that once you tear out the heritage, it is very hard to put it back. So what is remaining, thank goodness the remaining original school floor and our fourth floor Hall floor has never been touched since it was built (except for the lighting). In the seventies, the seniors moved downstairs and left upstairs alone, so they never made these more modern day renovations to the space, so we took their lessons and we insist on preserving the fixtures or the heritage that is original to the building when they bought it and built it in 1925. If you take it out and tear it out and replace it with something new, it is extremely hard to put it back.

$50,000 isn’t a lot of money in the building maintenance world. So, how much work are you facing?

We are facing a lot of challenges. Although there have been cosmetic fixes, we have yet to actually have a real deep dive into the condition of the building. There are signs in our foundation that there might be issues. We are sitting on what used to be False Creek, so the foundation issues are very apparent, and so the building does show signs that it’s like the floors are warping; that is actually one of my greatest concerns that I want to look into. The heating, it’s nice, its ok, but it is cold in that space, and we have a large archive, so temperature variation is not great for a hundred-year-old papers and documents that are sitting in the space, so there is that. There’s many, other things on that list that we have to tackle, but if we win the 50 grand, well, it’s a drop in the ocean, it is definitely a start, it is kind of a little bit of an encouragement for us to continue on to collect funds and hopefully one day down the road we’ll be able to have enough to actually start now.

What’s your pitch of why you should win?

The pitch is: Please save us because we are not just, like, we are a heritage building. We are one of 12 in Chinatown. I would say, we are quite impressive from the outside and the inside, we are all original from 1925. But it is not just about the old, it is also about whatever is going on now. We still, daily, the seniors are still there daily practicing their culture. The young people are getting more and more interested in the space, so we have more and more programming, that is not just new and modern, but also kind of paying homage to the old and we we find a happy medium to try to package the old traditions to a on younger next generation audience, so to continue doing that, we need our building to still be a hub in Chinatown for all these activities, so please Save Us.